There is a vast difference in student achievement scores within and among school districts across America. The reasons for these differences are many — and while some factors are beyond the control of the school district, many others are under their control. Teachers, principals, and administrators have long been implementing effective research-based strategies known to help students succeed.

Recent research has provided school boards with governance strategies associated with high student achievement. School boards should now consider changing the way they govern by implementing the prioritized actions detailed by the Board Standards (see the second article in the series, entitled “The Science of Student Achievement,” on page 12 of the May 2017 edition for more details). Boards should also consider addressing the nature of internal board relations (called “closure”) and external relations through interactions with the community (called “brokerage”). These actions are consistent with effective board governance and predictive of higher student achievement scores.

Beyond Opinion Researchers examining student achievement have focused their attention on students, teachers, classrooms, administrators, and school boards. These examinations provide opportunities to learn what happens to student achievement when various conditions exist. Whether a school is urban or rural, large or small, affluent or poor, ethnically homogenous or diverse, there are certain board characteristics common to school districts that report high student achievement. Understanding these characteristics and how they relate to student achievement helps form the building blocks of effective boardsmanship.

Research has shown that certain board behaviors, described by the Board Standards, are statistically related to high student achievement (Lorentzen, 2013). The Board Standards inform boards that their job is to look “up and out” while letting the administration deal with issues that are “down and in.” Effective school boards spend time on issues that have districtwide implications, such as ensuring accountability, setting high student expectations, governing responsibly, engaging the community, and creating the conditions for student and staff success.

Looking “down and in” is delegated to the superintendent, who deals with things such as teaching, sports, buses and transportation, student grievances, and personnel.

Reducing Board Disarray A school board that harbors wide disagreement about its proper roles and responsibilities is a board in disarray. When individual board members come to the board armed primarily with lay wisdom to guide their actions and decisions, it is little wonder opinions differ widely. Effective boardsmanship is not intuitive. There are appropriate and inappropriate ways to behave as an individual board member and as a collective board interested in improving student achievement.

One of the most important internal discussions a board can have involves coming to agreement about the board’s appropriate roles and responsibilities, as well as establishing expectations for the behavior of individual board members. Boards with low internal relations lack trust, don’t have a shared vision, display a lack of professionalism, and run the risk of telegraphing to the community that the district is equally unprincipled. To protect against these negative issues, some districts adopt a code of ethics, or code of conduct. Others develop a district plan, to which the Board Standards refer many times. (Editor’s note: New Jersey has the mandated Code of Ethics for School Board Members.)

The District Plan Many districts have strategic or long-term plans. While potentially beneficial, such plans too often have little practical utility because they are routinely shelved after being written. The district plan, on the other hand, is broader and contains two specific parts. The first part is the traditional strategic plan, which makes reference to multiple issues affecting the district. Typically, strategic plans don’t refer to the board but rather articulate long- and short-term goals that others within the district are held responsible to accomplish.

The second part is the board plan, which is written by the board to help guide its own actions. The board plan makes assurances to the public and district employees about how the board will govern the district. This plan should be consulted when making decisions, setting policy, allocating funds, creating initiatives, setting goals, and monitoring progress. It sets expectations that all students can learn, holds the administration accountable for making progress, and vows financial support toward this end. It is also a living document that sets district standards and expectations of how students, teachers, administrators, and the board itself are expected to function.

The board plan can be published online or in the local newspaper as an open letter to the community. Boards may choose to read pertinent portions of this plan at the beginning of each meeting or prior to voting as a reminder of what commitments have been made.

When properly developed and utilized, the two parts of the district plan become the rudder that steers the district forward each month while simultaneously reminding the board to delegate distracting issues to the superintendent.

Maintaining Focus While most districts have committees focused on finance, curriculum, facilities, and personnel, it is recommended by several organizations that school boards add a committee on governance, whose task includes making sure the board continues to function according to the district plan. This committee is responsible for locating the pertinent policy or statement in the district plan that justifies an agenda item as a board issue. If such a reference cannot be found, the issue is delegated to the superintendent. In addition, it is recommended that the agendas for monthly board meetings include items of districtwide importance, such as community engagement, student achievement, and board development.

The use of a preplanned annual calendar also stipulates, in a proactive manner, what district reports, trainings, and community group interactions are planned. Using such a calendar can keep the board focused on issues important to district governance, effective boardsmanship, and student achievement.

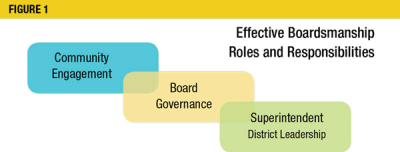

Only the Board The school board has two overarching responsibilities only it can perform: engaging the community and collaborating with the superintendent (see Figure 1). There are some things only the board can do. There are some things only the community can do. And there are some things only the superintendent can do. Understanding these clear distinctions can help the board function more efficiently and effectively.

Only the Board The school board has two overarching responsibilities only it can perform: engaging the community and collaborating with the superintendent (see Figure 1). There are some things only the board can do. There are some things only the community can do. And there are some things only the superintendent can do. Understanding these clear distinctions can help the board function more efficiently and effectively.

For example, only the community can send its children to the school, vote in elections, volunteer at the school, and offer candidates for the school board. Only the board can adopt the budget, construct and maintain facilities, make levy and bond requests, hire and evaluate the superintendent, engage the local community on matters of official district governance, and evaluate its own performance. Only the superintendent can be the district CEO; make recommendations regarding personnel, policy, and budget; provide the board with requested information; oversee the educational program; carry out policy; and make progress toward student achievement goals.

It is also important to recognize that there is an appropriate amount of overlap in these roles, where community and board, as well as board and superintendent, work together. Districts that respect and enact these roles and responsibilities govern districts with the highest student achievement scores.

Elitist boards ignore the community. Micromanaging boards steal responsibilities from the superintendent. Boards showing deference to the superintendent abdicate their responsibilities. These undesirable board behaviors, evident of inappropriate overlap, can eventually result in frequent superintendent turnover, which by itself is related to lower achievement scores (Alsbury, 2008). Effective boards recognize their appropriate overlap of roles and responsibilities with both the community and superintendent and also understand and respect the autonomy within each role.

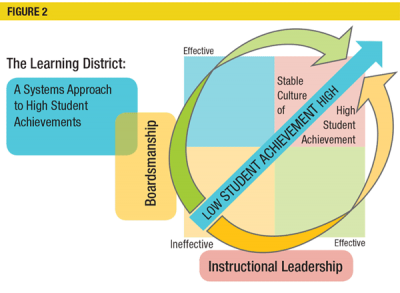

Districtwide Improvement Efforts There are two ways student achievement is often addressed: one, by focusing narrowly at the level of the classroom or school; and another, by focusing more broadly at the level of the district (see Figure 2). When districts rely solely on teachers or principals to address achievement, the effort is vulnerable to personnel changes or uninformed decision-making by the administration or board. On the other hand, when efforts to improve student achievement are addressed districtwide, there is a greater chance of transforming the entire district.

Districtwide Improvement Efforts There are two ways student achievement is often addressed: one, by focusing narrowly at the level of the classroom or school; and another, by focusing more broadly at the level of the district (see Figure 2). When districts rely solely on teachers or principals to address achievement, the effort is vulnerable to personnel changes or uninformed decision-making by the administration or board. On the other hand, when efforts to improve student achievement are addressed districtwide, there is a greater chance of transforming the entire district.

This approach is broader and more stable but may be more difficult to launch because it necessarily requires both effective boardsmanship (involving the governance team of board and superintendent) and instructional leadership (involving the instructional team of superintendent, principal, and teacher). The superintendent, of course, is an integral part of both the governance and instructional teams. Districtwide improvements in student achievement can be transformational, and therefore lasting, when boardsmanship and instructional leadership work simultaneously to address achievement in their respective ways. The transformation is not necessarily easy or quick, but districts have successfully accomplished it. It begins when the district decides the status quo is no longer acceptable.

Becoming a Learning District The beneficial effects of professional development are hard to overstate. While all states have education, certification, and professional development requirements for teachers and administrators, comparable requirements for school board members vary from state to state.

Once again, boardsmanship is not intuitive. Becoming a master teacher and accomplished administrator is the result of education, certification, and experience. Boardsmanship can be approached similarly. The National School Boards Association and TASB encourage all board members to participate in ongoing board training by attending conferences, participating in workshops, and holding study sessions to become better informed about governance issues facing the district.

Participating in professional development should not be optional for anyone involved in public education, including the board. And when everyone in the district takes advantage of ongoing training opportunities, works together, and learns together, then the district is becoming a Learning District. School districts are complex, organic organisms that succeed only when all parts of the system gain new information and understandings and begin to learn and improve together.

What We’ve Learned

- There is a developing science to effective boardsmanship. You no longer have to guess.

- The actions of school boards affect student achievement.

- The Board Standards describe elements of boardsmanship statistically related to high student achievement.

- The board is responsible for districtwide student achievement scores.

- The board’s two most important relationships are with the community and the superintendent.

- A board in disarray cannot govern a district toward high student achievement.

- Micromanagement harms student achievement scores, as does deference to administration.

- Engaging the community is an often overlooked but vital responsibility of the board.

- A district plan, containing the strategic and board plans, helps inform the district’s actions.

- When everyone in the system learns together, a Learning District can emerge.

Final Thoughts School board members are elected community members who volunteer to help govern the local school. Without guidance, board members have only intuition and personal experience to guide their decisions – which result in significant diversity between and among boards along many dimensions.

This series of four articles has advocated replacing board behaviors relying on intuition and personal opinion with behavior supported with research and recognized as best practice. These articles also advocate following the lead of boards who govern districts with the highest student achievement scores. These boards are doing something right, and they have things to teach us all. We do not claim to describe the one and only way to raise student achievement, but lessons can be learned from the most successful districts.

At this point in time, we are convinced that (a) implementing Board Standards, (b) enhancing internal board relations, and (c) improving external community relations are the best ways for a board to conduct business in order to improve student achievement districtwide. What we’ve suggested is a forecasting model based on the most current research. All districts should become Learning Districts. We hope the suggestions described here were helpful and trust that these ideas will be further refined as more research is conducted and important discussions continue.