That is the central question that school board members and school administrators confront every year at budget time, as they wrestle with the reality that the cost of running a school district has tended to increase more each year than the 2 percent tax levy increase that is permitted by New Jersey law. It is also a question that crops up whenever school districts learn of a new initiative or requirement from the state and federal government.

So school districts are understandably upset when state and federal governments create new requirements, without providing the amount of funding necessary to implement them. “Boards and superintendents are so hard-pressed today to provide a top quality education with limited resources,” says Dr. Lawrence S. Feinsod, NJSBA executive director, who served as a superintendent of schools for the Cranford, Madison and Mount Arlington school districts. “Unfunded and underfunded mandates place handcuffs on the ability of a district to develop a budget that provides for the needs of the children in their educational care.”

Background The relationship between local school districts and the state and federal governments has often been a source of friction since 1875, when New Jersey constitutionally guaranteed a “thorough and efficient” system of public schools. The Legislature has delegated the responsibility to carry out that function to local school districts.

Over the years, school districts and municipal officials grew frustrated with the state and federal mandates that came with no funding to implement them. In the November 1995 general election, the state’s voters approved the “State Mandate, State Pay,” amendment to the New Jersey Constitution. The enabling legislation for the amendment was effective in May 1996, and the law made it unconstitutional for the state to impose unfunded mandates on taxpayers. This year marks the 20th anniversary of when that constitutional amendment went into effect.

The amendment and enabling legislation also created the Council on Local Mandates, a unique entity that is independent of the executive, legislative and judicial branches of state government. The council determines questions of whether a particular governmental action established after the 1995 Constitutional Amendment is an impermissible, unfunded mandate.

The NJSBA Study Twenty years after unfunded mandates were prohibited, how are New Jersey school districts faring? NJSBA recently undertook a study seeking an answer to that, by looking at the more common phenomenon of “underfunding.”

“Unfunded mandates are clearly precluded by the constitution,” says Michael Vrancik, NJSBA director of governmental relations, “but underfunded mandates also create huge drains on district spending.

Underfunding would include instances in which the state and federal governments have created new requirements for local boards of education but have not provided the total amount of funding necessary to implement them. The 2016 NJSBA study focused on several areas, including enforcement and monitoring of the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights; preparation for, and implementation of, the PARCC assessment; special education; the AchieveNJ evaluation system; and Workers’ Compensation requirements.

Underfunded mandates, like unfunded mandates, include some worthy initiatives, however the lack of adequate funding hurts their effectiveness. “Most of these are well-intentioned programs, but chronic under-funding presents a financial burden to school districts,” says Dr. Lawrence S. Feinsod.

Key to the NJSBA study was a statewide survey of school board presidents, superintendents and school business administrators, which was issued in April 2016. In all, 204 educational leaders responded to the survey. Some 30.6 percent of the state’s operating school districts are represented in the survey responses.

The impact of underfunded state and federal requirements should not go unnoticed by state and federal lawmakers. The NJSBA report provides examples of new requirements accompanied by only limited resources and how they have placed a burden on local boards of education.

THE ANTI-BULLYING BILL OF RIGHTS

Nothing is more critical to the academic and emotional well-being of students than a safe and secure learning environment. Ensuring such a school climate is the goal behind the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights, which took effect in the 2011-2012 academic year. As important as this goal is, the state has not provided sufficient funding to enable school districts to implement the law without having financial consequences on other district operations.

Nothing is more critical to the academic and emotional well-being of students than a safe and secure learning environment. Ensuring such a school climate is the goal behind the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights, which took effect in the 2011-2012 academic year. As important as this goal is, the state has not provided sufficient funding to enable school districts to implement the law without having financial consequences on other district operations.

The act greatly expanded an existing law concerning harassment, intimidation and bullying (HIB). Among other things, the 2011 act required districts to establish bullying prevention programs and to train school personnel and others regarding those programs; required every school principal to appoint, from currently employed school personnel, a “school anti-bullying specialist” and every superintendent to appoint a “district anti-bullying coordinator” and to “make every effort” to appoint a current employee to that position; and required the formation of a school safety team in each school “to develop, foster and maintain a positive school climate,” whose members must include at least one teacher employed in the school and the school anti-bullying specialist.

The law also created a Bullying Prevention Fund “to offer grants to school districts to provide training on [HIB] prevention and on the effective creation of positive school climates.”

During review of the legislation, the Office of Legislative Services (OLS) could not determine the cost of implementation “as the cost would be contingent on decisions made by the state and local school districts that cannot be predicted.”

The net result of the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights Act was significant cost to local school districts. Heightened sensitivity to HIB increased the reporting of such incidents to unprecedented levels. According to the New Jersey Anti-Bullying Task Force’s first interim report, more than 13,000 incidents were reported in the first academic year following enactment of the law. The resulting responsibilities raised the positions of anti-bullying specialist and anti-bullying coordinator to full-time jobs in many school districts.

Meanwhile, the Bullying Prevention Fund went unfunded.

Council on Local Mandates Decision In 2012, the Allamuchy Board of Education filed a complaint with the Council on Local Mandates, which decided in its favor. Allamuchy had incurred a one-time cost of $6,000, plus $1,000 annually, for the implementation of an anti-bullying program by a third-party vendor. Additionally, because the anti-bullying coordinator, specialists and safety team members were members of the local bargaining unit, the district anticipated additional compensation of $2,000 to $4,000 for each of these staff members, depending on their responsibilities.

As a result of the Allamuchy decision, the state appropriated $1 million for the Bullying Prevention Fund in 2012-2013 and 2013-2014. However, the program has not been funded since then, and no appropriation has been recommended for next school year.

According to the New Jersey Anti-Bullying Task Force, the $1 million was woefully inadequate to meet school districts’ needs statewide. In the its 2016 annual report, the task force noted that 2013-2014 requests to the NJDOE for bullying prevention funds totaled approximately $9 million.

NJSBA Surveys That figure is consistent with a 2012 NJSBA survey of business administrators. In that survey, 206 business administrators (representing 40 percent of all school districts statewide) identified more than $2 million in additional costs in their districts to implement the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights, including costs for supplies, materials and software, for professional development, for additional programs, and for additional staffing.

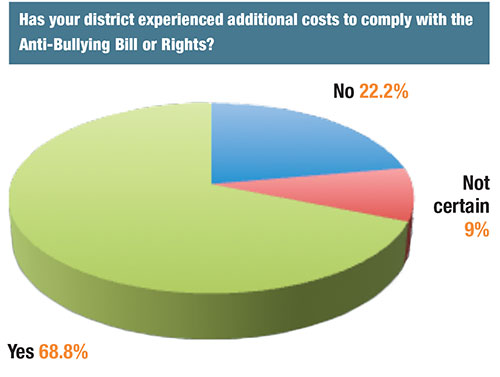

NJSBA’s April 2016 survey shows that the law continues to place financial and administrative burdens to districts. When asked if their district had experienced additional costs to comply with the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights, 68.8 percent said yes, 22.2 percent said no; and 9 percent were not certain.

School officials were also asked to indicate the areas in which their districts experienced additional expenses. The four most frequently cited areas were as follows:

- Professional development, indicated by 90.1 percent of respondents;

- Programs/initiatives, selected by 60.3 percent;

- Supplies and materials, 52.1 percent, and

- Personnel, 50.4 percent.

Just below 10 percent of the survey participants cited “other costs,” with legal fees noted by several respondents.

In most cases, the additional costs are of a recurring, or annual, nature.

The PARCC Assessment

In 2014-2015, New Jersey transitioned from its former NJASK and HSPA assessments to the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) assessment in mathematics and English language arts. As opposed to its predecessors, PARCC is a computer-based assessment. Therefore, many school districts had to expend funds on technology in preparation for the new PARCC exams.

More than 90 percent of the respondents to NJSBA’s April 2016 survey indicated that the PARCC assessment resulted in additional expenditures to their school districts.

NJSBA believes that a uniform statewide test (or an alternative method of measurement) should be used to assess student progress toward state academic standards. To help school districts prepare for, and administer, the new PARCC assessment, the Association established programs to enable the purchase of technology at lower cost, and provided information, based on statute and code, addressing schools’ responsibilities in administering the statewide tests.

The April survey of board presidents and business administrators confirmed the need for assistance in securing technology.

| PARCC-Implementation Expenditures | |

|---|---|

| Expenditure | Cited by… |

| User hardware (e.g., laptops, tablets, etc.) | 90.6% of respondents |

| Infrastructure upgrades | 89.4% |

| Other types of expenditures: Staffing (substitute teachers, personnel to oversee testing, stipends), training, software, consulting services | |

In 2014-2015 and 2015-2016, the state provided assistance through a new funding category, PARCC Readiness Aid. At $10 per student, this new categorical aid provided $13.5 million annually for local districts “to procure the technology necessary to offer the online PARCC assessments.”

NJSBA’s April 2016 survey indicates that, for most districts the aid level did not meet the level of expenditures for PARCC preparation and administration. When the survey queried, “Did the cost of PARCC preparation and implementation exceed $10 per student?” nearly 65 percent of respondents said yes, while 32.2 percent were “not certain.” Only 3.3 percent said no.

Among the survey respondents who indicated that PARCC expenses exceeded $10 per student, the actual costs cited for implementation ranged from $15 to $2,000, with an average of $236 per pupil and a median of $250.

The criticism of PARCC as an underfunded mandate is tempered by the recognition that, in many school districts, technological upgrades were needed for academic programs, and that their benefit will go beyond the assessment. Close to 90 percent of respondents said their districts would have made at least some of the technological upgrades even without PARCC.

In March 2015, the state indicated that it planned on spending $108 million over a four-year period for the PARCC assessment. (The $13.5 million in PARCC Readiness Aid was not included in that figure.) Additionally, the state education department has made a financial commitment to digital learning the Future Ready Schools-NJ initiative, a partnership with NJSBA and the New Jersey Institute of Technology.

SPECIAL EDUCATION

No discussion of underfunded mandates is complete without addressing special education, a federally and state-required service that, in many respects, has been a success story in New Jersey public education – but, nonetheless, a costly one for local school districts.

In its Policies and Positions on Education, NJSBA calls for state funding of the “full excess cost” of special education services – that is, special education expenditures that exceed those for general education. Current state and federal funding practices, however, place an undue burden on local school districts, and their property taxpayers, to support this state- and federally-required program.

NJSBA Research A 2007 NJSBA-sponsored study found that, in Fiscal Year 2005, the annual cost of services for 232,894 students with special needs totaled $3.3 billion statewide. Local school districts supported 57 percent of the costs, with the remainder coming from state funds (34 percent) and federal aid (9 percent), according to the study.

The research identified the main cost-drivers as out-of-district placements, programs for students with autism, transportation, related services, and resource programs. Other factors included high classification rates and impediments to shared services. The NJSBA study reaffirmed the need for a fair, adequate and equitable funding formula.

In 2014, another NJSBA project culminated in the report, Special Education: A Service, Not A Place. The study reflected more than a year of research by a task force that included board of education members, state officials, and school administrators and other educators. Citing New Jersey Department of Education data, the task force found that special education costs continue to outpace inflation.

Expenditures identified as special education increased approximately 8 percent from 2008-2009 to 2011-2012. The increase was twice as large as the rate of growth in expenditures for general education. They were also double the rate of growth in the special education population during the same period.

In 2011-2012, statewide expenditures to cover the additional costs of serving special education students accounted for over one-fifth of the total expenditures for K-12 education.

From 2008-2009 to 2011-2012, the number of classified students in regular operating districts (i.e., those that did not have the former “Abbott” designation) grew by 4 percent, while total enrollment in those districts remained flat. During the same time period, the number of special education students in the former Abbott districts remained flat.

The percentage of students in the former Abbott districts who are taught in the most restrictive settings is more than double that of regular operating school districts.

A New Formula The School Funding Reform Act of 2008 altered the method of distributing state aid to local school districts, including the funding of special education.

Previously, all special education funding consisted of “categorical” aid – an allotment per pupil related to the services needed and provided to each district regardless of community wealth. The SFRA changed the distribution method, rolling two-thirds of special education funding into a district’s wealth-based “equalization aid” and providing one-third as categorical aid.

In calculating the special education component of equalization aid, the formula uses a state average percentage of classified students, rather than the district’s actual number of students with special needs. For 2016-2017, the “Educational Adequacy Report,” a periodic reassessment of the factors used in the SFRA formula, set the statewide classification rate at 14.92 percent, with an additional 1.63 percent of students qualifying for speech therapy.

Additionally, the SFRA limits a district’s special education categorical aid by factors such as the statewide average classification rate, average statewide cost and regional cost adjustments

The shifting of two-thirds of special education funding to a wealth-based formula has increased the underfunding of this state-required program in many districts. Additionally, by using statewide averages, rather than the district’s actual special education population and costs, for both the wealth-based and categorical components, the current formula further increases the financial burden of this state-required service for many communities.

Extraordinary Costs State law calls for additional funding to help districts pay for “extraordinary” special education costs – that is, those expenditures above a certain per-pupil amount. The latest Educational Adequacy Report recommends reimbursement of extraordinary costs as follows:

- In-district placement – 90 percent of the amount above $40,000 per pupil

- Placement in another public school district – 75 percent of the amount above $40,000

- Private school placements – 75 percent of the amount above $55,000

Local school officials note the limited nature of extraordinary special education costs. A survey conducted as part of NJSBA’s 2014 report, asked the question: What changes in law or regulation would enable your school district to better manage special education costs without affecting program quality and availability? Frequently cited was the need to “[e]xpand expenditures covered by the Extraordinary Special Education Aid.”

Federal Funding for Special Education When the federal special education law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), was enacted in 1975, the federal government promised to cover 40 percent of the cost of implementing required special education services. However, the amount covered by federal funding has been considerably less.

According to data from a February 2015 report by the National Education Association, federal funds covered only 16 percent (or $357.7 million) of New Jersey’s IDEA costs. If federal funding were provided at the promised 40 percent level, the state would have received $893.4 million in IDEA funding in 2014-2015. That higher funding level would have resulted in an additional $535.7 million in federal special education aid for New Jersey.

A number of school districts have been required – sometimes by court order citing the IDEA – to provide separate placement for students, often in private settings that involve residential and travel costs. Such extraordinary special education costs can have a dramatic impact on an individual district’s budget, making it difficult to accommodate the required service without affecting general education and other programming. For these school districts, the issue of IDEA funding at the originally promised levels, along with adequate state support for extraordinary costs, is particularly acute.

2016 Survey NJSBA’s most recent survey on unfunded and underfunded mandates posed an open-ended query to give respondents the option to describe “other unfunded and underfunded mandates affecting your school district.”

The most frequently cited requirements involved special education, or related areas such as special education class-size limits and out-of-district placement. Cost estimates include $40 million annually for all special education services in a large K-12 district in central New Jersey; $500,000 for special education programs in a small elementary district in Monmouth County, and $400,000 in a Bergen County elementary district.

TEACH NJ

TEACHNJ/AchieveNJ In August 2012, Gov. Chris Christie signed the first significant reform of the state’s century-old teacher tenure law. The legislation, the Teacher Effectiveness and Accountability for the Children of New Jersey (TEACHNJ) Act, received unanimous approval in the Senate and Assembly.

TEACHNJ/AchieveNJ In August 2012, Gov. Chris Christie signed the first significant reform of the state’s century-old teacher tenure law. The legislation, the Teacher Effectiveness and Accountability for the Children of New Jersey (TEACHNJ) Act, received unanimous approval in the Senate and Assembly.

Tenure Reform The law increased the amount of time – from three years to four – that a new employee needed to serve in his or her position to receive tenure protection. Among other changes, the statute placed adjudication of tenure charges with an arbitration panel, rather than the commissioner of education.

TEACHNJ required the development of an evaluation system with four summative ratings – “highly effective;” “effective;” “partially effective;” and “ineffective.” Significantly, it tied retention of tenure to the evaluation process.

The keystone of these reforms is a statewide evaluation system, titled AchieveNJ and established through state regulation. AchieveNJ incorporated uniform standards of student growth into the annual performance reviews and mandated a minimum number of observations and evaluations each year.

The New Jersey Department of Education guide to AchieveNJ provides details on the process:

“Teacher evaluation consists of two primary components: Teacher Practice (measured primarily by classroom observations) and Student Achievement (measured by Student Growth Objectives and, for a select group of teachers, Student Growth Percentiles).”

“Teacher practice is measured by performance on a state-approved teacher practice instrument (e.g., Danielson, Marzano, et al.), which is used to gather evidence primarily through classroom observations.”

Since the mid-1970s, NJSBA has advocated replacement of lifetime tenure with renewable contractual tenure. The Association expressed its support for the tenure reform provisions of TEACHNJ as an important step in ensuring the quality of instruction. NJSBA also supports the inclusion of student achievement data in employee evaluations.

Costs to School Districts While NJSBA supports the purpose of TEACHNJ and AchieveNJ, it has concerns about the administrative time and expense required to implement the evaluation process in light of statutory financial constraints.

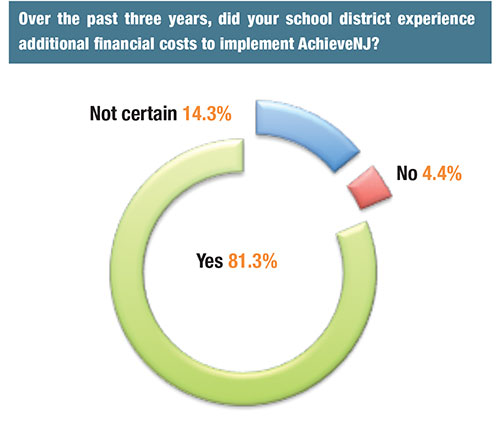

The vast majority of school board presidents, superintendents and school business administrators participating in NJSBA’s survey on underfunded mandates indicated that their districts experience additional costs in implementing AchieveNJ.

Over three-quarters of the respondents identified licensing fees for the district evaluation model (e.g., Danielson, Marzano) as the reason for additional expenditures. For 33.1 percent of the respondents, the additional expenditures recur annually; 57.4 percent indicated the costs were both recurring and one-time. Examples of annual cost estimates include: more than $240,000 in a 15,000-student K-12 district; $10,000 for a southern New Jersey elementary district with fewer than 750 pupils; and $125,000 for a 5,000-student K-12 district in suburban northern New Jersey.

The survey asked school officials if the additional costs negatively affected other programs. Just under half (49.1 percent) said there was no negative impact. Those who indicated a negative impact were given a list of program areas and asked to identify those affected. Generally, responses were evenly divided among curriculum development, the instructional program, extracurricular activities, and counseling.

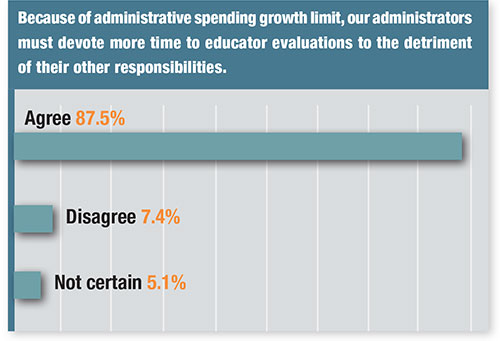

Nonetheless, respondents agreed that the evaluation process has taken a toll on the time administrators have available for other responsibilities, particularly in light of statutory administrative spending limits.

Because of administrative spending growth limits, our administrators must devote more time to educator evaluations to the detriment of their other responsibilities.

| AchieveNJ: Reasons of Additional Expenditures | |

|---|---|

| License for the chosen evaluation model | Cited by 78.2% of respondents |

| Software | 65.3% |

| Equipment/supplies | 42.9% |

| Additional administrative staff | 38.8% |

| Additional clerical staff/overtime | 19.7% |

| Training/professional development | 17.7% |

WORKERS’ COMPENSATION

Current statute requires that school boards pay a school employee full salary for up to one year when the staff member is absent from work due to an employment-related injury. The full-salary requirement is unique to school districts. Other New Jersey employers are required only to provide employees with 70 percent of their salary, pursuant to the New Jersey Labor and Workers Compensation Act.

Current statute requires that school boards pay a school employee full salary for up to one year when the staff member is absent from work due to an employment-related injury. The full-salary requirement is unique to school districts. Other New Jersey employers are required only to provide employees with 70 percent of their salary, pursuant to the New Jersey Labor and Workers Compensation Act.

The school-specific mandate has been in place since 1967 (P.L.1967, c.168). Prior to that, the law stated that a school board “may” provide “up to” full salary. As a result, local school districts, unlike other public and private employers, must pay an amount in addition to state-required workers’ compensation benefits that is equivalent to 30 percent of the employee’s salary.

Costs per district for this benefit can fluctuate annually. The financial impact in any given year would be difficult for a district to anticipate. Nonetheless, it can be significant, given the number of districts that pay workers’ compensation claims, according to NJSBA’s survey.

The survey asked respondents to estimate how much their districts paid “out of pocket” to fund claims over the past three years. Most respondents said they were not certain of the amount. Of the 25 who did offer estimates, the three-year average expenditure was $380,470.

Individual responses varied widely, however, and may illustrate the difficulty school districts face in predicting these costs. Examples include the following: $1.5 million (central New Jersey K-12 district, with approximately 9,000 students); $200,000 (Morris County K-12 district, with over 2,000 students); $75,000 (Bergen County K-12 district, with over 1,200 students); and zero (Atlantic County K-8 district, with over 3,000 students).

NJSBA Recommendations

In its report, NJSBA issued seven recommendations for action to minimize the impact of underfunded mandates:

Boards of education are urged to adopt resolutions calling on state and federal officials to provide adequate funding of required programs. NJSBA provides sample resolution language at staging.njsba.org/unfunded-mandate-resolution.

- Working with the National School Boards Association, NJSBA will advocate the interests of students and local school districts, including the provision of adequate federal funding, when Congress begins reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

- NJSBA will continue to seek fair and adequate state special education funding and, at the same time, will advocate for an adjustment to the 2 percent tax levy cap for special education cost increases.

- NJSBA will seek legislation to make workers’ compensation requirements for local school districts consistent with those of other New Jersey employers.

- NJSBA will continue to provide school districts with opportunities to secure the technology necessary for implementation of standardized testing and digital learning.

- NJSBA will continue to monitor the financial impact of the Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights, AchieveNJ and other well-intended, but underfunded, state requirements on school district budgets.

- NJSBA will continue to seek relief from the administrative spending growth limits, which affect the ability of school districts to carry out responsibilities under AchieveNJ.

- The text of the entire report can be found at staging.njsba.org/underfunded-mandates2016.