Over the past two decades, a movement has been coalescing that blends “technophilia,” hacker culture, social media, and traditional arts and crafts. It has brought together cooks and quilters, drone pilots and pianists; and is epitomized by television shows such as Mythbusters, Shark Tank, and Chopped; and on Discovery, Etsy, and Pinterest.

It’s called “maker culture” and, increasingly, people from all walks of life are travelling and paying to experience it in person: the World Maker Faire in Queens, N.Y., for example, drew more than 100,000 participants last fall.

Whichever the platform, what attracts people to “making” is the inspiration to attack challenges with imagination, creative uses of tools and materials, and often reckless abandon. Maker events and places create physical and virtual pop-up open-source think tanks in a society where new discoveries are often thought of first for profit.

And now, perhaps most excitingly, maker culture has moved into schools.

From STEM to the Maker Mindset Judith Ramaley of the National Science Foundation is credited for coining the term STEM in 2001 to promote science, technology, engineering, and math in schools, as a way of training students to remain globally competitive. Since then, many have discovered the benefit of an even greater integration of content areas, but a traditional school structure, in which learning is segmented by subject and bell schedules, can be a barrier. Adopting a maker mindset wipes the slate clean and enables educators to rethink everything about school design.

If there is a single element that can serve as a content bridge, it is technology. Yet schools tend to go about tech selection and implementation backwards, buying first and thinking of good uses second. The most common idea of technology – computing devices, peripherals, and the web – narrows our imagination. The original and broader meaning serves us better, stating that technology is:

The application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes; the use of science in industry, engineering, etc., to solve problems.

Rather than any particular platform or gizmo, purpose is the heart of the real definition. In maker classrooms, problems are solved more often with clay, glue guns, saws and soldering irons than with apps, smartboards, or 3D printers.

Technology Use is Key Research affirms that the way technology is used is more important than what technology is purchased. Dr. Ruben R. Peuntedura’s SAMR model of technology integration helps assess teacher use, describing a simple evolution from substitution to augmentation to modification, and finally to a redefinition level in which technology allows us to teach in ways we couldn’t otherwise – a lofty goal! Similarly, the Moersch Levels of Tech Integration (LoTI) scale, developed by Dr. Chris Moersch in 1994, looks at student and teacher applications, moving through awareness, exploration, infusion, integration, and expansion, to refinement.

Rather than just contemplating how tech is implemented, it may be more useful to consider student needs. Like Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” a framework describing human motivation, at its lowest level, technology can bring a sense of comfort and familiarity to digital natives. Then, it can spark interest and even engagement; connect students to each other and the world; and ultimately foster independence. Because good tech is individually adaptive, it can also level the playing field – provided we don’t increase the digital divide by offering opportunities that some students can’t take advantage of, such as flipped classrooms.

How Does the Maker Mindset Fit in Schools?

It’s Accessible Technology may be the only commodity that gets less expensive as it provides greater capacity. A tiny flash card with 1000 times the memory of a five-pound hard drive from the 1980s can be had for ten bucks, rather than several hundred. This inverse cost/capacity ratio is part of the maker revolution; it has democratized innovation and been a boon to startups and schools. For the price of a desktop computer system, a school can buy eight Chromebooks. Robots can be built from scratch with a $10 Arduino clone at their core. Most kids over the age of 12 have the world’s knowledge in their pocket in the form of a cell phone, and so – with some staff training and tweaks to acceptable use policies – BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) can enable schools to dispense with textbooks.

It Helps Students Master Learning Standards New standards have challenged educators not only to teach differently, but think differently. The Next Generation Science, technology, career, and Common Core standards view content as more integrated and emphasize real-world connections and practical applications.

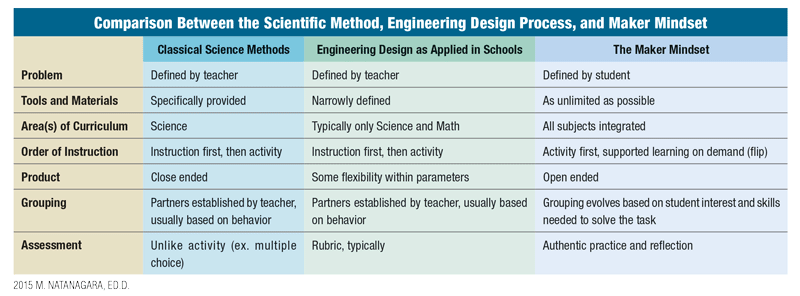

The table below compares the stereotypical form of science taught since the 1950s (which bears little resemblance to the true process of scientific discovery) and engineering activities some publishers claim are more problem-based. By contrast, the maker mindset is content-neutral and, as authors Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe phrased it, focuses on the “big ideas,” getting to the core of what each subject area is about rather than specific facts, numbers, procedures, formulas, names, and dates.

It Supports the Whole Child The maker mindset not only addresses standards more holistically, it is more engaging, more personalized, and more practical. Students identify problems themselves and bring their own experiences and interests to bear. Making is individually expressive and personally meaningful, but it is also nearly always collaborative. It speaks to diverse learning styles and brain theory; reflects popular culture and student interests; represents real world applications and a focus on solutions; and helps brings equity (for example, gender-based, and income-based) to the classroom. Every experience in a unit plan created with a maker mindset – field trips, research, mentors, group tasks – is designed to contribute to success in solving the problem.

It Better Prepares for the Future There’s still a place for vocational programs fostering specific skill sets. But increasingly, businesses require employees who are creative, analytical, global, outside-of-the-box thinkers. Makers are future inventors, entrepreneurs, designers, engineers, programmers, and problem solvers – skill sets welcome in any organization.

How School Districts Can Take (or Make) the Next Step Most schools have probably already moved toward more hands-on lessons and integrated tech tools, and curriculum has been revised to reflect new mandated standards (at least on paper). Next, schools need to take a hard look at activity design and teaching practices. These don’t happen in a vacuum; the best way to make changes is from the ground up. Let people experience making.

Despite the classic stereotype of the scientific method, innovation seldom takes a linear path. Likewise, the road to a maker mindset needn’t be in any particular order, and won’t look the same in every classroom, school, or district. As with all worthwhile endeavors, districts need to decide upon their particular destination.

Developing makerspaces in schools doesn’t have to cost a lot, either (more on that later.) Here are some suggestions on how your district may get started.

Clarify Your Mission Odds are, any district sets goals each year related to student achievement, engagement, lifelong learning, culture, climate, and college and career readiness. Goals drive curriculum, resource allocation, hiring, training, budget priorities – just about everything. The act of defining a mission is a bonding experience. The New Jersey School Boards Association organizes goal retreats for just such a purpose. Having these discussions helps develop support – or “buy in” – among administration, board members, staff, and community,

Participate in Events – Then Create Your Own The best way to understand the maker mindset is to engage in it. If it’s impossible to get to a major Maker Faire, search the web for “maker events,” “EdCamp,” and “makerspaces.” Teacher, administrator, and school board conventions increasingly provide school and community members with opportunities to learn about STEAM, problem-based learning and open-ended hands-on activities.

In the Toms River Regional School District, staff began by participating in state and national initiatives such as the Hour of Code and N.J. Makers Day, which have websites to support activities, and at tech and teaching workshops at EdCamps and Rutgers University, which were free or charged minimal fees. From there, district professional development began to model the maker ethos, with teachers sharing with peers, and moving away from lectures to hands-on professional development.

If staff is regularly attending such experiences, it’s time to organize one! Toms River created the Jersey Shore Makerfest in 2015 and 2016, each of which drew over 4,000 people. That’s a big leap from being one of a hundred at an EdCamp, but the district did it for free by convincing sponsors of its community value. More than 100 maker volunteers (some big names included) provided experiences and materials.

Just putting together an event benefits an organization, by clarifying and building excitement about your mission; identifying and sharing skills and resources within your organization, some of which you may not have known existed; and creating new, and solidifying existing, partnerships and bonds with your community.

Build Spaces for Making According to makerspace.com, “Makerspaces represent the democratization of design, engineering, fabrication and education.” Districts needn’t have the perfect space in order to implement the maker mindset into every classroom or a single shared area.

To engage in maker activities, you should have as diverse a selection of tools and materials as possible. Because space and resources will be based on particular needs at the time, access to materials, and the skill set of the people in the room, there is no one model for the ideal makerspace – not even a “best practice.” Here are some examples of spaces Toms River created, and steps taken in order of complexity and budget:

- Moving materials from cluttered closets into clear bins on pushcarts, sorting by item rather than purpose.

- Consolidating books to free up sections of libraries, then adding areas with simple maker tools and materials, to turn them into true multimedia centers.

- Emptying computer labs of old desktops, replacing them with Chromebook carts (at a quarter of the price), and building centers for Lego robots, Scratch programming, green screen video, and augmented reality.

- Completely revamping woodshops – with staff, student, and community input – to make room for Arduinos, 3D scanners and printers, and CNC machines.

The Finance Factor Makerspaces needn’t cost schools an arm and a leg. While the Toms River Regional School District has invested over $300,000 creating makerspaces, the estimated cost of each space varied – from $10,000 to $50,000.

Partnerships help. The Toms River district converted an outdated woodshop at an intermediate school to an “Innovation Station” with the donation of $60,000 in furniture and technology from Office Depot, a partner at the district’s Makerfest event. The district’s facilities team put in an estimated $15,000 worth of construction and remodeling.

Donations of supplies and smaller scale items go a long way, too. Put the word out to your community, and you will be deluged by donations of Legos, tools, cardboard, PVC pipe, paint, material, etc. (and often the talent that comes with them.)

Think big and wide on grants; last year, Toms River won over half a million dollars’ worth of grant money to support STEAM initiatives such as makerspaces, labs, and a Title I summer makercamp.

Ready, Set, Make. Actually, Just Make. Don’t worry if you’re ready. Perhaps the biggest fear of many teachers and administrators is the perceived loss of control. Sometimes, lessons may turn into lively events that a teacher may feel the need to apologize for – but it is often in such seemingly chaotic settings that real learning takes place.

In Toms River, one of the elementary schools held a STEAM night that drew over 600 parents. Several school media centers in the district are open at lunch and after school for robotics clubs and tinkerers. Schools can invite knowledgeable artists, builders, engineers, and innovators from the community into classrooms as mentors, advisors, guest teachers and speakers. A simple change can be to tweak existing science activities to make them more open-ended.

Rather than asking how to build a bridge that will hold a car, ask how to get a car over a chasm. You’ll discover that all students are makers at heart, and the greatest reward is seeing students discover solutions they – and we – never imagined.