Chances are, of the nearly 600 public school districts in the state of New Jersey, your district does not have a director of technology. Or if it does, chances are this individual’s title is not “director of technology.”

In smaller districts, the role and technology responsibilities may belong to a principal, a computer or tech coordinator, or a manager of operations technology. In larger districts it may be a supervisor, a chief information/technology officer, or even the superintendent.

Many school districts seeking to advance their use of technology, or take on a major technology project such as a one-to-one initiative, may desire to create the leadership position “director of technology.” But rather than attach specific role responsibilities to such a title, it might be more beneficial to think of the staff member in a district who plays the role of the “district technology leader,” or DTL, and who is responsible for building district technology capacity.

“District technology capacity” is the ability of a school district to adopt, integrate, and routinely use technology to benefit teaching and learning. Research suggests there are three crucial elements to building district technology capacity: 1) setting vision, also known here as visionary leadership, 2) funding, and 3) facilitating conditions, including professional development. History suggests every school district needs a district technology leader – a DTL – to spearhead these three elements, in order to build needed capacity. Accordingly, it is important to understand the crucial role, responsibilities and activities that must be assigned to a DTL, regardless of the title used, and to consider how a current DTL role needs to change in order to build a successful, long-term, district technology capacity.

Participating in the District Visionary Leadership First, and in recognition of the rapid pace of technology change, visionary leadership in a school district requires fluent, short-term, intermediary negotiations set by the central district leadership team. Working collaboratively at the district leadership level, with input from the board of education, the leadership team must use relevant data to develop and promote a district vision – the desired future of increasing educational technology capacity – in a way that inspires and stimulates commitment to achieving this longer-term goal.

Research is definitive here: Visionary leadership is the most important element for a successful technology initiative. The National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA), the organization that sets standards for district administrators, suggests of visionary leadership, “in collaboration with members of the school and the community, and using relevant data, develop and promote a vision for the school on the successful learning and development of each child and on instructional and organizational practices that promote such success.”

In regard to the responsibilities of the DTL, participating in the visionary leadership process at the cabinet level, to provide technology knowledge and input, is crucial for building successful technology capacity over time.

Steering Funding to Support the Vision District leadership co-creates and drives the vision, which in turn drives the first requirement of any successful initiative: funding. By allocating necessary financial resources, the district demonstrates commitment to the vision and the initiative. Further, researchers have found that a unified vision, supported through prioritized district finances, when placed within the role of the district leadership team, positively influences teachers to adopt and integrate technology.

Yet, building a long-term funding commitment to technology capacity is remarkably hard in New Jersey. On an annual basis, approximately 75 percent of any school district budget goes towards salaries and benefits. Much of the remaining must be allocated to fixed costs such as food service, transportation and energy. With what is left, the district leadership team must fund school supplies, building maintenance, and technology purchases. Districts with successful one-to-one initiatives may allocate up to an entire 2 percent of the district budget alone to ensure success.

Given that the majority of superintendents serve just a few years in a district, the long-term funding of such an initiative must be robust and compelling enough to commit short-term financial positions, exposed to annual surplus and deficit cycles, to transcend a superintendent. In many cases, this long-term commitment must also outlast the terms of many school board members.

This implies that another major role of the DTL is to provide long-term institutional knowledge; the DTL must spearhead institutional plans, such as the district technology plan, and activities such as forming a technology sub-committee of the board, and offering community stakeholders positions on a district technology committee. These activities can provide an institutional knowledge base that continuously re-educates the district and community, over time, in a way that affords an adherence to these financial commitments.

For the DTL, then, participating in the district financial decision-making process is a never-ending, long-term activity, that requires a vigilant, annual line-item budget commitment in service of the district’s strategic plans and the higher vision to which the district leaders are mutually committed.

Directing Facilitating Conditions In successful technology initiatives, after a needs assessment, organizations build technology capacity by funding tangible and outward demonstrations of organizational support. Research has established that these demonstrations – or technology-facilitating conditions – include technology systems and infrastructure; technology support (help desk staff); equitable distribution of technology; professional development; peer mentoring and coaching; administrative support; curriculum revisions; and professional learning communities.

Exploring any one of these topics in detail is beyond the scope of this article. Yet it is important to note that building and directing all of these successful facilitating conditions has a direct and positive influence on encouraging staff members to adopt, integrate, and routinely use technology for teaching, learning, and communications. As Barbara B. Levin and Lynne Schrum emphasized in the Journal of Research on Technology in Education in 2013, “not addressing every piece of the puzzle simultaneously may produce unintended outcomes and will certainly slow down efforts for school improvement” and technology initiatives.

Current Role Expectations – Dramatically Different from the Past The DTL, actively directing and prioritizing these facilitating conditions in the K-12 environment, is a relatively-new phenomenon in school districts. In the business world, the recognition, support, and inclusion of a chief technology officer, or chief information officer, has been an expectation for about the last 20 years. Gordon Hunter wrote about these expectations in the Journal of Knowledge and Technological Development Effects on Organizational and Social Structures in 2013, stating that these staff members were to act like apostles carrying “messages about the capabilities of information technology and its productive application for competitive advantage” throughout their organization.

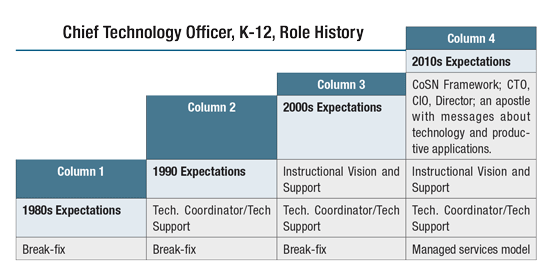

The DTL in the education world has taken a more roundabout path, as shown in the table above.

The 1980s was a time of computer experimentation, where the forerunner of the DTL was expected to install individual computers and software. This tech role did not require an instructional certification, networking or server knowledge or expertise. The role changed in the 1990s, as the internet and networks permeated districts, and required more expertise.

In the early 2000s, as expectations grew for students to learn 21st century skills, DTL expectations grew to include instructional expertise as well as operational support. Today, in the era of big data and assessments, expectations for Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) and one-to-one initiatives, as well as the growing expectation of integrating technology use over time, role expectations for the DTL have become even more intensified and diversified. The expectations of today’s DTL are similar to that of the business world, in that this staff member must go beyond being a leader spearheading the structure for facilitating conditions. To successfully build technology capacity, the DTL must participate in visionary leadership, ensure robust facilitating conditions, and participate across organizational boundaries united in one systemic effort.

Researcher Anika B. Anthony also recognized the importance of boundary-spanning in interactions between the DTL and other administrators, such as the director of professional development, and specialists for core content areas, for successful integration and utilization. Thus, embedded in research is the acknowledgement that the role of the DTL must engage all leaders on the district leadership team in activities that span cross-organizational boundaries to successfully and routinely utilize technology.

From Past to Future The legacy of the DTL role, then, parallels the legacy of computer development, from a self-contained computer box, or the “break-fix” computer tech of the 1980s, to the role of the complex organizational systems leader of today. Today’s DTL role is fundamentally different from the siloed, self-contained tech departments of the past. It requires an empowered district leader to act like an apostle carrying messages about virtual field-trips, Google Expeditions, or asking experts to join classrooms for question and answer sessions through video-conferencing.

As far as appointing a staff member to the DTL, this newer role is one that most building-level leaders (such as principals) find difficult to fill. Research has indicated that these individuals do not usually have the technology knowledge, or the time, to be comfortable or successful in this districtwide technology role.

Likewise, chances are that an outside consulting agency does not have the institutional knowledge or long-term commitment to bring about a true increase in technology capacity that will be a good fit – technically and culturally – for a district. Building facilitating conditions over time requires that a successful DTL recommends, purchases, deploys, maintains, replaces, and steers the professional development towards successfully adopting, integrating, and utilizing the technology on a routine and ongoing basis.

Certifying DTL Success The Consortium for School Networking (CoSN) has the only recognized district technology leader certificate, the Certified Educational Technology Leader (CETL). This certificate is earned by passing an exam made up from ten domains. Within these domains, it becomes apparent that parts of the DTL role include managing three organizational technology branches:

- information;

- networking/communication systems, and

- information systems (staff and student) and data management. A successful district technology organization model recognizes the staff members assigned to each of these branches – even if it is only a single staff member.

A fourth, equally important role, is the manager of instructional professional development, a role charged with both creating and running professional development offerings. This individual also shares and educates staff district-wide about innovative and best practices of technology use in such a way that successful models are diffused, and adopted more readily. Otherwise a district simply ends up with pockets of technology excellence.

With current expectations of building increasing technology capacity in a school district, the assumption follows that the position cannot be shoehorned into the historical responsibilities of simply purchasing, deploying, and maintaining technology. For the DTL to fully participate in vision setting, and successful long-term technology adoption, many managerial tasks must be delegated to others in the district.

Only in this way can the DTL participate in the collaborative role expected to meet the needs of today’s district enterprise systems.

So, what is the role of your district DTL/director of technology? It is defined by the activities and initiatives that are woven into your district strategic and technology plan. It is a role charged with ensuring routine, daily, mission-critical operations of the district; as well as the success of any district initiatives such as a one-to-one. As such, it shares a place on the district leadership team participating in visionary leadership. It requires a long-term commitment of annual funding to support building crucial and successful facilitating conditions. It is a district leadership role charged with both co-creating a districtwide compelling vision to increase district technology capacity, and ensuring that district facilitating conditions, directing and managing both the operations and instructional technology programs, are met to ensure successful organizational diffusion and adoption of technology.

Stated differently, we know that if there is no DTL or change agent to bring about visionary, participatory, or distributed leadership; if there is no organizational member tasked with making a case for districtwide technology change; a member who can successfully advocate and negotiate crucial funding, build an organizational culture of facilitating conditions, and encourage capacity building – then adopting, integrating, and routinely utilizing technology will not be successful in a district.

Who fills the role of the director of technology in your district?

Get a complete list of references.