According to the data from the National Center for Education Statistics, salaries and benefits make up 80 percent of the current operating expenditures in the average New Jersey school district. Even in the wake of monumental New Jersey public sector benefit reform and the Affordable Care Act, health insurance costs continue to rise at a faster pace than other compensation costs. In fact, for most school districts, at a much faster pace. Over the past six years the annual premium increase for the School Employees Health Benefits Plan (SEHBP), a plan that more than half of local boards of education are enrolled in, has been at least double and in some years, five times the average collective negotiations settlement for New Jersey teacher bargaining units. (See table below. Note: Settlement rates are based on a July 1 to June 30 year; SEHBP increases are by calendar year.)

These extraordinary increases have taken place in a complex reform environment. Some of these reforms have provided some relief and others present tough challenges for boards.

Understanding these reforms can help boards fashion workable bargaining strategies to assist in remaining fiscally and educationally sound. There have been two major waves of reform; state reform and the Affordable Care Act on the federal level. Let’s start with the state reforms.

State Public Sector Insurance Reform In the 2009-2010 school year – the last before the state reforms kicked in – only 13 percent of the contracts analyzed by NJSBA had any employee contribution at all. In 2010, for the first time, New Jersey law (called Chapter 2) required board employees to pay for a portion of their insurance. Specifically, it required school employees to pay 1.5 percent of their base salary toward health benefits, regardless of whether coverage is provided through the SEHBP or a private insurance carrier. That law also allowed districts to negotiate provisions that restrict employees’ plan options within the SEHBP. For instance, districts could negotiate that their employees would participate in SEHBP but disallow the selection of the richest plan, NJDirect10.

The next year, Chapter 78 required school employees to pay a portion of health insurance premiums. The exact amount of the employee share is a function of the employee’s salary and the plan that they choose. Depending on plan choices and salary, the employee contribution ranges from 3 percent of the premium to 35 percent of the premium and is never less than 1.5 percent of the employee’s base salary.

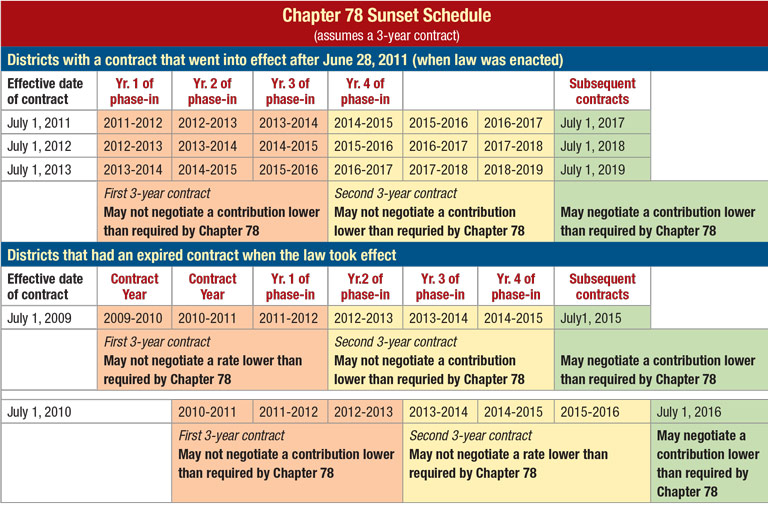

Unionized employees did not have to start the new contributions until the collective negotiation agreement that was in force when the law was enacted (June 28, 2011) expired. The employee contribution has a four year phase-in period. In the first year, the employee pays a quarter of the employee contribution requirement and that percent is increased an equal percent amount in the next three years until in the fourth year, the employee will pay the entire contribution called for under Chapter 78.

The employee contribution component of the law expires after the four-year phase-in is complete. Districts and their employees are bound by the contribution levels required in the law until the contributions are fully phased-in and in effect for an entire calendar year.

For many districts, now in or approaching negotiations, the four-year phase-in will be completed soon. The table below shows when your district may begin negotiating health benefit contributions.

When the parties are negotiating the next collective negotiations agreement to be executed after Chapter 78 sunsets, the board and the union are legally permitted, but in no way obligated, to negotiate some other cost-sharing arrangement. Remember, to reduce employee contributions below those required under Chapter 78 requires the approval of the board. The board can say no and the fully phased-in employee contributions are the status quo for negotiations purposes.

The 2010 and 2011 laws helped many districts to financially tread water as health care costs escalated. These changes to the insurance environment were not taking place in a vacuum. The tax levy cap is an important element.

Two Percent Tax Levy Cap In 2010 annual property tax levy increases by local boards of education were capped at 2 percent. The 2 percent cap does allow an adjustment for extraordinary increases in health care costs. It is important to understand that, practically, the cap does not provide a one- for-one adjustment, however. It allows for adjustments as follows: the actual increase in total health care costs for the budget year that exceeds 2 percent but may not exceed the average percentage increase of the State Employee Health Benefits Program. What that means it that if the SEHBP average percent increase is 10 percent, the allowable adjustment would be capped at 8 percent. It’s also important to remember that new contributions from employees towards health benefits will reduce the actual increase in total costs, and therefore the allowable adjustment.

Negotiability of Health Insurance Coverage Health insurance is a significant cost driver in local school districts and has historically been a critical part of the collective negotiations process. Health insurance is a mandatory topic of collective negotiations with unions. Issues such as the level and type of insurance coverage, employee eligibility, payment obligations, etc. are all topics for negotiations.

Not all insurance issues, however, are subject to negotiations. The New Jersey Public Employment Relations Commission (PERC) has long held that the identity of the carrier, in and of itself, is not a term and condition of employment, and thus not negotiable, as long as the selection of the carrier does not change or modify employees’ levels of benefits. Therefore, negotiations over health insurance is limited to the level of benefits, but the choice of the carrier remains a board function that is not subject to negotiations as long as the choice does not change the level of negotiated benefits.

Most bargaining agreements have a standard of comparison negotiated into the contract. Frequently, the parties will agree to coverage that is “equal to or better than” a certain plan. For instance, “equal to or better than the School Employees Health Benefits Plan.” The “equal to or better” than standard is not advantageous to the board. Better standards that provide more flexibility to the board are the “substantially equivalent” or “comparable to” standards.

Any modification in school employees’ type and level of coverage, any change in employee eligibility, any change in the obligation to cover the costs of coverage, and even the addition of a new benefit, must be the result of an agreement reached between the board and the union at the bargaining table.

A huge part of negotiating health benefits, like negotiating other terms and conditions of employment, is preparation. The starting point is figuring out how much the district is currently spending on various medical insurances. The employee benefits package represents a substantial and growing cost item for every district in the state. Just like costing out the salary guide, it is imperative that as part of the preparation for negotiations process, the board cost out its benefit package. With the help of your business administrator, you should determine the current cost of benefits, the anticipated increased cost of those benefits and the cost of any proposals affecting benefits.

A recent law change helps districts considering leaving the School Employees Health Benefits Program. Signed into law in 2013, P.L.2013, c.189, mandates that once every two years the SEHBP provide, at no cost, complete claims experience data to boards participating in the SEHBP. The bill requires the SEHBP to provide the complete claims information in an electronic and manual format to the board within 30 days of receipt of a written request. This is invaluable information that the board can use to shop the insurance market.

Although a majority of districts participate in the state plan, it is worth noting that participation in the SEHBP is highly controlled by statute or regulation. Boards enrolled in the state plan cannot negotiate over many aspects of insurance coverage that are negotiable when insurance is purchased from a private carrier. Boards in the state plan cannot negotiate over the design of the insurance coverage, the deductibles, the co-pays, or covered services. The state plan, in those respects, is a “take it or leave it” proposition.

A full in-depth understanding of all your insurance coverage options requires knowledge of a range of existing possibilities. This includes information about the design of insurance plans and the factors that drive the cost of premiums. It includes an awareness of all the various types of coverage on the market, as well as the potential for cost increases or savings. Few board members or school administrators have the breadth of experience and expertise necessary to make well-informed decisions specifically tailored to fit the district situations. In this increasingly complex environment the expert assistance of an insurance consultant can assure that the board has explored and considered all the short and long-term implications to various types of insurance coverage. Insurance consultants can also be a resource at the table or in explaining certain negotiations proposals to the union or rank and file employees.

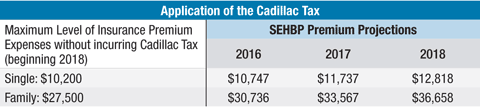

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires schools with 50 or more employees to offer health insurance to employees who work a certain number of hours. The offered plan must meet minimum standards of affordability and coverage. In 2018, the ACA will penalize employers whose health plans exceed certain maximum standards. The penalty, known as the “Cadillac tax,” is an excise tax on annual insurance expenses that, in 2018, exceed $10,200 for single coverage and $27,500 for family coverage. The threshold applies to total cost; it matters not what portion is paid by the employer and what part is paid by the employee.Cadillac Tax For districts that are continuing negotiations or are going into negotiations this fall, another consideration is the looming “Cadillac tax.” The Cadillac tax is a provision of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that is slated to take effect in 2018. The Cadillac tax was included in the ACA to offset costs, to help slow the growth rate of medical costs and to pay for other reforms.

Employee unions will maintain that the Cadillac tax will not be implemented as planned in 2018. And, there are some possible factors that speak to that. Between now and 2018, there are numerous intervening elections and there are provisions in the Cadillac tax that may allow for adjustments for particularly high-risk employee pools. Nonetheless, districts will need to plan for the implementation of the Cadillac tax. Given the current trajectory of health care inflation and no congressional “fixes,” the potential financial impact on local boards of education is enormous. Here’s why: 55 percent of New Jersey school districts participate in the School Employee Health Benefits Program. The vast majority of school employees participating in the SEHBP choose the richest plan offering, NJDirect10. For the 2016 plan year NJDirect10 single coverage costs $10,747, while family coverage is $30,736. Since 2011, the average rate of growth in the SEHBP premiums for active employees has been 9.21 percent. Assuming that the trend continues, and there is no further reform, premiums will rise over the next three years as shown in the table on this page.

That would mean that $2,617 of each single premium and $9,158 of each family premium would be over the threshold and subject to the Cadillac Tax. Or put another way the district would have a “Cadillac tax” liability that amounts to $1,047 for each employee with single coverage and $3,663 for each employee with family coverage (40 percent of the coverage).

Another consideration is that the tax applies to the overall aggregate cost of employer-provided health insurance – including the contributions made to FSAs (Flexible spending accounts). Since Chapter 78 mandates that boards of education establish an FSA to allow employees to set aside, pretax, a portion of earnings to pay qualified medical expenses, this too must be considered when estimating the financial impact of the tax. (See IRS Code, 26 U.S.C. 125).

In terms of collective bargaining, there are numerous ways to address this. First, when figuring out what the parameters for settlement are, the district will have to carefully consider what the implementation of the tax in 2018 will mean for the district’s operating budget. In terms of actual contract language, the district can propose a provision that allows the district to unilaterally move to a compliant program.

An example of that language is below:

“If the medical and prescription drug combined plan’s premiums exceed the threshold of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s (“PPACA”) Cadillac Tax (as implemented) the parties must agree upon a new plan that will not require an excise tax payment pursuant to the PPACA Cadillac Tax within thirty (30) days of notification being given to the Association. Otherwise the board will charge back to the employee the dollar value of the excise tax incurred to the board.”

Another option is to provide for a reopener clause that specifies that in the event the Cadillac tax is implemented, the parties will meet and engage in good- faith bargaining to arrive at a sustainable health care plan.

Waiver Incentives Another potential cost-saving measure is a waiver incentive for employees not to take insurance. Waiver incentives are financial incentives provided by school districts to employees in exchange for those employees foregoing the insurance coverage provided by the district. Under state law, boards of education participating in the state plan can, without negotiations, offer a financial incentive for employees not exercising their rights to enroll in the insurance plan. Boards can unilaterally offer employees up to 25 percent of the amount saved by the board as a result of the employee’s non-enrollment or $5,000, whichever is less. The law specifically directs that, within the legal limits above, the amount of the waiver is to be established “in the sole discretion of the employer.” Thus, the clear language of the statute not only authorizes waivers in the state plans, but preempts the entire issue from being the subject of negotiations for boards that participate in the SEHBP. By contrast, incentives for non-enrollment remain a negotiable topic for boards that obtain their health insurance coverage from a private carrier.

If the district provides its insurance through a private carrier, the rules and considerations are different. First, incentives for non-enrollment in private plans are just like any other term and condition of employment – a topic that must be negotiated with the union.

Another consideration when districts procure private insurance is the potential for waivers to negatively affect the “experience rating” of the district. The “experience rating” is used by insurance companies to predict a district’s future medical costs based on its specific past experience (i.e., the actual cost of providing health care coverage to the district during a given period of time, or the district’s claim history). Thus, the insurer calculates the district’s insurance premium based on its own, not the overall community’s, experience. In contrast, the SEHBP uses a “community rating” approach. Under this approach, higher-cost groups (e.g., districts that are made up of relatively older or sicker people) are averaged out with lower cost districts (e.g., districts made up of relatively younger or healthier people). The expenses of all participants are pooled together and then spread out equally across all participants. Sometimes when districts offer waiver incentives to staff participating in private insurance plans, the relatively young, healthy employees take the waiver leaving a riskier insurance pool with a higher experience rating. This can mitigate the anticipated savings. Since the SEHBP is a community-rated plan, who takes the waiver and the underlying riskiness of the individual school’s employee pool does not affect the district’s renewal rates.

Since 2010, the law bars individuals from being covered under more than one SEHBP and/or SHBP program. For example, an individual who works for the state may not receive SHBP at his work and also be covered by his spouse’s SEHBP provided by a local board. Likewise the district cannot pay an individual to waive SEHBP coverage if they are still receiving coverage under the SEHBP or SHBP under their spouse’s plan.

Given the partial sunset of the Chapter 78, the ever-escalating insurance premiums, the complexity of the Affordable Care Act’s Cadillac tax, and the nuances of waiver incentives, providing your district’s employees with health insurance is a more complicated and expensive task than ever. Districts would be wise to seek advice from an insurance consultant, as well as NJSBA’s labor relations staff when negotiating a new contract. Additional resources are also available at the NJSBA labor relations webpage.